The study that just won’t die: disfluency edition

This is a story about a study that refuses to die, despite overwhelming evidence it should.

From a new article in HBR on using behavioural science when rolling out AI tools:

Consider building an AI transcription tool. It would be reasonable for designers to assume that the most seamless interface is always best. But behavioral research shows that intentionally adding a little friction—e.g., displaying words in harder-to-read font—actually helps people scrutinize the text more closely, which helps them find and correct errors.

That claim traces back to a classic paper by Adam Alter and friends (2007).1 In Experiment 1, Alter and friends gave students the cognitive reflection test. Here’s one question:

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost? _____ cents

The questions typically have an intuitive, wrong answer and a correct answer that requires a little more thought. In this case, the intuitive (wrong) answer is 10 cents. The correct answer is 5 cents.

Alter and friends split the experimental participants into two conditions. Some participants were given the questions in an easy-to-read font, others in a hard-to-read font. And as suggested in the HBR article, those who were given the questions in the disfluent font answered more questions correctly. Sixty-five percent of participants in the disfluent group got all questions correct, compared to only 10 percent in the fluent condition.

The paper has a series of other similar experiments in which they show that disfluency can trigger more analytical forms of reasoning, sometimes correcting the errors of intuition.

This all sounds good until we examine the follow-up studies that have come in since.

Thompson et al. (2013b) ran a series of experiments on disfluency, including three involving the cognitive reflection test, and found no effect on accuracy. They did suggest there might be an effect among the highest-IQ participants, but nothing in aggregate.2

Then Meyer et al. (2015) ran replications testing disfluent fonts and the cognitive reflection test across 13 labs. Combining those 13 replications with the three by Thompson and friends and the original study by Alter and friends brought the total sample size up to 7,365 people (from the original 40). The headline finding was there was no effect of disfluent fonts. Further, there was also no effect when the analysis was restricted to only the higher-IQ participants.

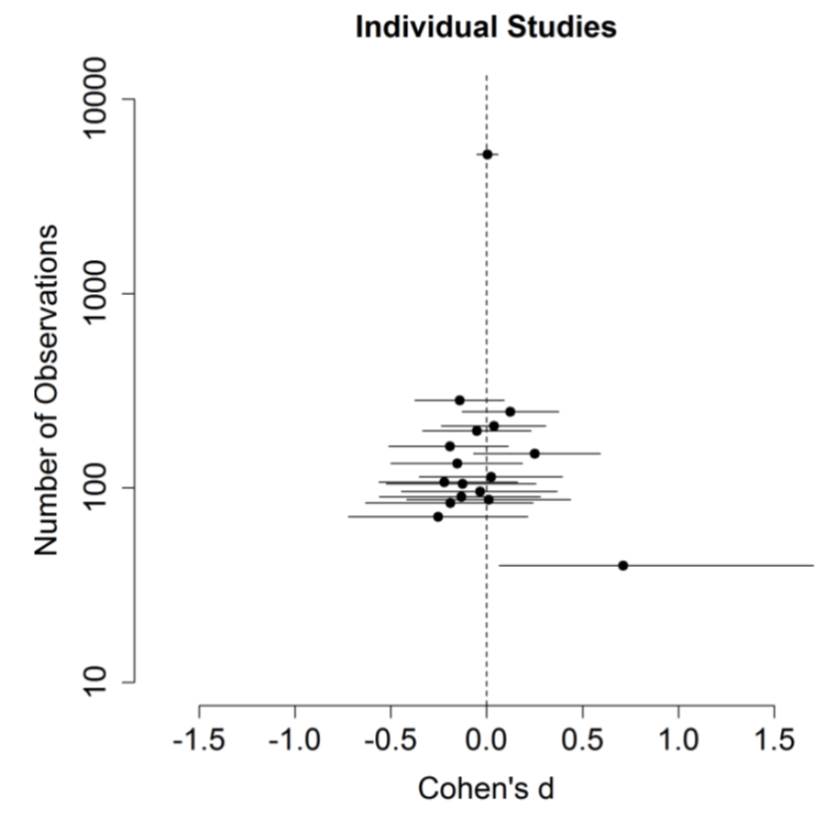

This diagram highlights the stark contrast between the original study and later attempts to replicate. The pooled result (top dot) shows no effect, with the dot centred on zero with a very narrow confidence interval. The 16 individual replications below it tell the same story. Only the original study, isolated at the bottom right, shows an effect.

Finally, the Many Labs II project (Klein et al., 2018) also included Experiment 4 from Alter and friends’ paper in its replications. That experiment involved syllogistic reasoning problems. Alter and friends found their 41 participants did better with disfluent fonts. The Many Labs II replication found nothing. This wasn’t unexpected: a prediction exercise in advance of the replication gave it a 42% or 32% probability (using survey or market estimations) of replicating (Forsell et al., 2019).

Back when Meyer et al. (2015) was first published, Terry Burnham suggested we should measure the rate of learning via citations. In April 2015, Terry Burnham suggested we measure learning via citations. The original Alter paper had 344 citations then, while Thompson’s replication had 38.

To November 2025, the trend hasn’t been great. Alter’s paper now has 1,442 citations (up 1,000+), while the replications have grown to 349 and 139. The original study is still being cited far more frequently than the evidence it doesn’t replicate.

When people ask me why behavioural economics and behavioural science are still fringe disciplines in applied settings, I have many suggestions. One is this absence of quality filter. The shiny stories get told again and again no matter how much evidence accumulates that they are rubbish. That lack of filter eventually gets found out.

I’ve been beating this drum for almost 10 years now. Sadly, it still needs beating.

References

Footnotes

This wasn’t the paper linked from the HBR article. The link is to a review by Alter and Daniel M. Oppenheimer (2009) on disfluency affecting meta-cognition. There is no statement about disfluent fonts affecting accuracy or error correction in that paper. However, of the papers referenced in that review, the claim about hard to read fonts improving accuracy comes from the Alter et al. (2007) paper.↩︎

There was some back and forth between Alter et al. (2013) and Thompson et al. (2013a) about how to interpret the replication, but the headline of no improvement in accuracy remains.↩︎